Overview

In 2019, rural America is a place that many discuss and debate but few actually understand well. In the minds of much of the citizenry, it is often a mythic realm, its boundaries and terrain defined by pop cultural imagery and datelines from small towns — amber waves of grain in front of an old red barn punctuated by a news account from a region defined as Appalachia.

As conversation grows about how to address or “fix” the challenges in the nation’s rural places, such a simple interpretation will no longer do.

The geographic, demographic, and socioeconomic landscape of rural America is remarkably diverse. Depending on the community in question, rural America can be hilly and remote, or it can begin at an exit off an interstate with flat lands stretching to the horizon. Its racial and ethnic composition can look like America from 50 years ago, or it can be ahead of the demographic changes that are reshaping the country. Its economy might be driven by tractors and commodity prices but more often by small factories and the retail trade.

Rural America, in other words, is not a monolith. Its wide-ranging, evolving communities have different strengths, face different trials, and need different policy solutions.

This report from the American Communities Project (ACP) at The George Washington University uses data and on-the-ground reporting to explore those differences and blow up the mythology that too often has come to define rural America. The analysis here, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, should inform the growing discussion about the “urban/rural” divide by showing the enormous complexity underpinning the phrase “rural America” in 2019.

The work here reinforces the idea that where you live matters a great deal to how long and how well you live, even within areas collectively defined as rural. It also explores misconceptions about the relationship between health and geography. Cross-analyzing data, including numbers from the County Health Rankings and Roadmaps, Gallup, and Simmons Consumer Research, the American Communities Project’s work here illustrates the gaps in opportunities for health.

Overview Index

Major Findings

Demographics

Economics

Infrastructure: Real World and Virtual

Daily Life

Health-Care Gaps

Well-Being and the Future of Rural America

The ACP Rural Universe

The term “rural America” is not a simple one to encapsulate. Depending on your source, there are densely populated urban metropolitan areas that hold rural terrain and, thus, could be considered rural America. At the same time, there are some definitions of rural America that exclude small-town urban centers.

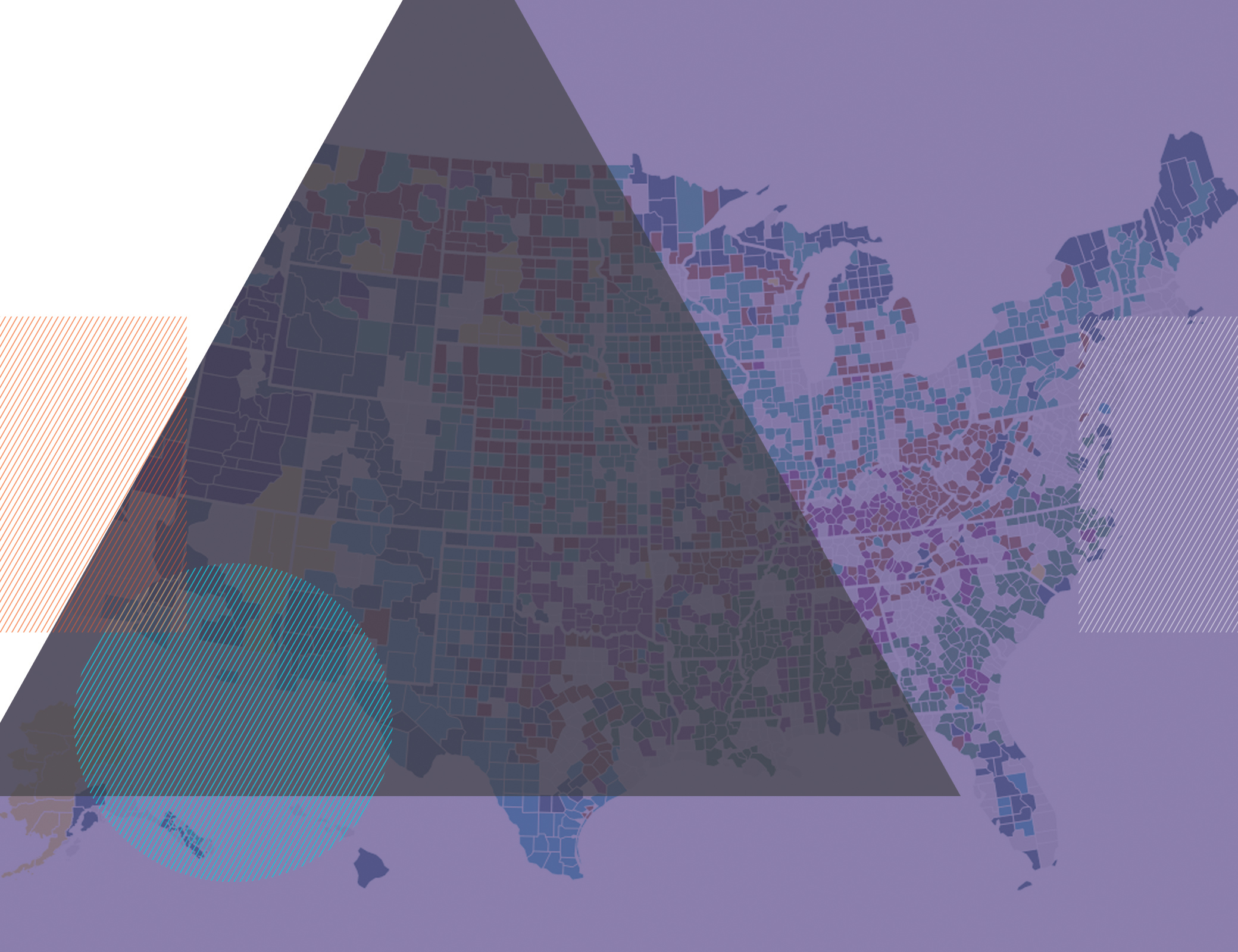

For this report, the ACP focuses on truly rural types of community, so we merged our county typology with the list of counties that qualify for rural health grants from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). In particular, we focus on the counties in which more than 80% of a given county falls into the HRSA rural definition. Our universe, therefore, is a collection of 2,243 counties in nine type categories scattered across the country. The universe is charted below.

The nine ACP types that are the most rural are:

- Racially mixed communities of the African American South,

- Sparsely populated Aging Farmlands,

- Culturally conservative Evangelical Hubs,

- Senior-heavy Graying America,

- Ethnically diverse Hispanic Centers,

- Mormon-populated LDS Enclaves,

- Sovereign Native American Lands,

- Small-town Rural Middle America, and

- Blue-collar Working Class Country

The map below contains the counties that are considered rural by the Health Resources and Services Administration definition as they fit into the nine rural community types of the American Communities Project.

Across our analysis of these communities, there are six major findings — and a list of important factors driving them.

Major Findings

- The physical and demographic landscape of rural America is remarkably diverse. While there is a tendency to view rural America as the cultural world portrayed in Grant Wood’s famous American Gothic painting — of a white farm couple posing with pitchfork in front of their farmhouse and barn — there are more than 500 rural counties in the African-American South, Hispanic Centers, and Native American Lands where the median white, non-Hispanic population is under the national average.

- The economic challenges and opportunities in rural America vary greatly. The average median household income in the rural Latter-Day Saints (LDS) Enclaves is roughly $55,000. In the African American South, it is less than $38,000. In the LDS Enclaves, the childhood poverty rate is 15%. In the African American South communities, the rate is 33%, which is 11% above the rural median.

- Education matters. The three community types with the highest unemployment rates are also below the rural America average for some college education. The data suggest that, even with the immense diversity of rural America, improving education is key to a better life and more opportunity. A push toward extending educational expectations to community college could pay large dividends.

- There are stark differences in health care as evidenced in health insurance rates. In the rural Working Class Country, only 9% of the population is without health insurance. In the rural Hispanic Centers, the figure is 18%.

- Some parts of rural America are seeing dramatic losses in population, but other kinds of communities are growing. Nearly 80% of the rural communities in the African American South have lost population since 2010. But fewer than 50% of the rural counties in Graying America have lost population since then — and overall the population of those counties has grown.

- Infrastructure, real and digital. Across rural America, there is little correlation between population and paved roads. Some of the most densely populated places, such as the African American South, have fewer miles of road than the sparsely populated Aging Farmlands. Internet connections and speeds also look very different in different community types. In rural Hispanic Centers, 80% of the households have a high-speed Internet connection, but in Native Americans Lands, the figure drops to 40%.

These findings underscore the nuance and complexity of rural America today. The larger point behind all these differences, however, is simple. When policymakers and funders look to create rural-focused solutions, they should not focus on silver-bullet, one-size-fits-all answers. The diversity of rural America can be a strength, but it also means single solutions are unlikely to work in all rural communities.

A Snapshot in Data

Many of the differences outlined in the bullet points above can be seen on the interactive map below, click on a county or enter its name in the box to see how it compares to its larger rural type on a number of different factors.

The Nine Rural Community Types

= median of all rural counties

Population change 2010-2018

Percentage white, non-hispanic

Percentage uninsured

Percentage in fair/poor health

Percentage with at least some college education

Median household Income

Miles of road in county

Median home value

For the remainder of this chapter, we analyze data from the nine rural community types across five broad topics: demographics, economics, infrastructure, daily life, and health care.

In subsequent chapters, we explore the ACP rural landscape with profiles of six different rural communities we visited:

- two counties in Arkansas — Fulton (Working Class Country) and St. Francis (African American South);

- two counties in Kansas — Finney (Hispanic Centers) and Gove (Aging Farmlands); and

- two counties in the Dakotas — Todd, South Dakota (Native American Lands), and Morton, North Dakota (Rural Middle America).

These profiles put faces, voices, and real communities behind the numbers. We chose places proximate to one another to show how quickly rural America can change. You can get in a car in one kind of community and get out in a completely different one, all without leaving “rural America.”

In short, in data and on the ground, rural America looks nothing like the monolith it is often portrayed as in the media and in Washington.

We believe this report is a call for a new understanding about the complicated set of places that make up the majority of the nation’s land. The different community types we outline here hold different strengths and face different challenges. They are driven by different economies and different kinds of populations. Simply put, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to policies for rural America.

We hope this report is an important step toward people gaining that understanding.

Demographics

While rural America is often thought of as a sea of similarity — largely white and generally older than the country as a whole — the demographic look and feel can change on a short drive. The races and ethnicities that define one rural community can be very different from those in a rural community nearby. And while much of rural America has seen population declines, the drops are far from uniform. The differences are stark in the community types of the ACP.

Race and Ethnicity

On the most basic level, rural America, as defined in this report, is less diverse than the nation as a whole. The median county in our collection of 2,243 rural places is 87% white, non-Hispanic. The mean for all rural counties is 78% white, non-Hispanic, still less racially and ethnically diverse than the nation overall. (In the U.S., the mean is 60% white, non-Hispanic.) But the 2,243 counties look much more complicated through the prism of the ACP typology.

Among the 306 rural counties in the African American South, the median county is only 56% white, non-Hispanic. It’s also 36% African American, almost three times the national average. In the 153 Hispanic Center counties in rural America, the median locale is only 40% white, non-Hispanic. Meanwhile, it is 53% Hispanic, almost three times the national figure of 18%. And in the rural Native American Lands communities, 43 counties, the median county is only 29% white, non-Hispanic, while it is 59% Native American.

There are outliers in the other direction, of course. In the Aging Farmlands (161 counties), Working Class Country (321 counties), and Rural Middle America (551 counties), the median counties are more than 90% white, non-Hispanic.

The broader point in the data: The overall numbers for race and ethnicity in rural America mask key subtleties. Such distinctions mean that policymakers may need a more nuanced lens as they address the challenges in these communities. Outreach and approaches that work in Gove County, Kansas (95% white, non-Hispanic) may not work as well 87 miles away in Finney County (40% white, non-Hispanic). We visited both counties for this report, and you can read profiles of each in later chapters.

That diversity also means more attention needs to be paid to the racial and ethnic differences that can define rural communities. There is a tendency to think of “rural” as meaning small and homogenous. But in some communities, such as those in the African American South, there are historic divides that serve as deeply rooted challenges that need to be addressed and overcome. We saw that dynamic on display St. Francis County, Arkansas, where the community is digging in to address the issue.

Age

Another dominant media narrative regarding rural America: It is home to a rapidly graying populace. On the whole, the 2,243 counties we examined are older than the nation at large. Using the median and the average to measure the counties, 20% of the population is 65 years or older. That compares to an overall national average of 16%, a notable four-point difference. However, this does not capture the nuance at the community level.

In several of the communities we visited, we heard that finding licensed child care was a real challenge. The strains were particularly evident in Finney County, Kansas, the Hispanic Center we visited, where local leaders are working with existing child-care providers to become licensed child-care centers.

In the Hispanic Centers and LDS Enclaves, the median figures for the 65-or-older population (15% and 16%, respectively) are close to the national average. At the other end of the spectrum are Graying America and the Aging Farmlands, where the 65-or-older population of the median county is 24%. That’s a nine-point difference in the 65-or-older population in our rural types.

The data also show that, proportionally, large populations of young people are living in parts of rural America. The median counties for seven of the nine rural types sit at or above the national average for the population under age 18, 22%. And the overall rural median and average for that age group are exactly 22%. That suggests that a key challenge in these communities is holding onto people as they pass from adolescence to adulthood, when they graduate high school and plan their next life steps. Economic opportunity, or lack of it, plays a role in those numbers. We saw and heard this while visiting rural communities.

Importantly, the Native American Lands stand out for having an extremely young population. Only 12% are 65 or older and nearly a third are under 18. But those figures are deceptive. The reason for so few older people in those communities is a very high mortality rate. The life expectancy in the median Native American Lands county is lower than the medians for the other communities we examined.

Taken together, however, these age numbers underscore the larger point: Rural America is about more than navigating retirement plans and collecting Social Security checks. In some rural communities, child-care can be as much or more of a challenge than elder care. In others, concerns center on adult battles with depression and addiction. For most of these places, a major challenge is creating jobs that will enable them hold on to people in their prime working years.

Many Sizes and Densities of Rural

The many rural communities in the 2,243 counties explored here have diverse environments and the differences become clear when examining the populations. The median county in our rural county group has a population of 17,743, but the numbers across our collection of rural counties vary sharply, creating very different kinds of places.

The data on population also reveal that rural America may not be emptying out as quickly as some suggest. On the whole, 64% of the 2,243 counties in our rural group have lost population since 2010, but in terms of raw numbers, rural America has grown by about 1.4 million in that time. To be clear, that’s very slow growth. It’s a fraction of a percentage point compared with the roughly 63 million people who live in these counties, and it lags far behind the national growth rate of 6%.

More to the point, the story of population growth or decline varies greatly by community type.

Some types, such as the African American South, have seen widespread population losses, with 79% of the group’s counties losing population. But in other places, such as Graying America, fewer than 50% of the counties have declined. And in Graying America counties collectively, the overall population number has climbed by about 174,000 since 2010.

The population losses in rural America may be felt most strongly in the Aging Farmlands. Roughly 76% of those counties have lost population since 2010 and, perhaps more important, many started from a low baseline. That means further losses can have large impacts on local businesses and schools as well as local culture and mindset. Overall, the Aging Farmlands have declined by a mere 18,000 since 2010, but that number is enough to equal an almost three percentage point drop for the type.

The news media and popular culture often focus on the urban/rural divide, and the population density of urban areas does make those places different from their rural counterparts. But the data here make clear that racial and ethnic diversity is a large part of the story in rural America. In that way, the communities of rural America are not so different from the urban areas they flow around.

The depopulation trend impacting some rural counties is not radically different from the exodus to the suburbs that remade so many metro areas in decades past. And the racial tensions in some rural communities, such as those in the African American South, are not dissimilar to those in the nation’s urban centers.

In a broader sense, all the numbers here emphasize the need for a new understanding of rural America as a multidimensional and multicultural landscape that defies simple answers and definitions. For anyone looking to effectively serve these communities, it is vital to understand the racial and ethnic complexities within them.

Economics

For many rural communities, economic development sits at the heart of local concerns and planning. Analyses that show urban America driving economic expansion are not lost on rural chambers of commerce and neither are the forecasts that show the tech sector as an engine of future growth. But as the U.S. economy is being remade, the communities of rural America bring a diversity of backgrounds and strengths to the table. Their economic paths in the coming years will almost certainly be varied as well.

Income and Inequality

Probably no single indicator encapsulates the many different rural Americas more than median household income. The range in our 2,243 counties is massive. In some places, such as the LDS Enclaves and Rural Middle America, the median income ($54,900 and $53,200, respectively) are very close to the national median ($57,600) and above the median for our rural sample ($46,600). But other communities, such as the African American South ($37,900) and Native American Lands ($41,900), lag far behind.

It’s truly a complicated picture. That’s a range of $17,000 in household income in these different kinds of rural communities. Some of those differences may be due to regional cost of living, but those disparities don’t account for the entire range. In some communities, the differences in household income are more about steeper economic challenges and deeper historical deficits.

In some communities with large populations of color, there can be other economic disparities existing within a single place. Racial divisions are often seen as an ingrained part of urban America. Stories of white flight, redlining, and socioeconomic segregation are written into the histories of most major American cities. But those same divides can appear in rural locales. For instance, in St. Francis County, Arkansas, an African American South community we visited, the median household income for African Americans is only about $28,300, while the figure for whites is more than $10,000 higher at $39,500. And stories of white flight are deeply tied to it as well. In Finney County, Kansas, a Hispanic Center we visited, the median household income for Hispanics is about $42,300, while for white, non-Hispanic households it’s $61,600. And in that county, efforts are underway to foster dialogue across groups. For example, the Garden City Cultural Relations Board consists of seven members across racial, social, ethnic, religious, and economic backgrounds, which seek to promote cultural diversity.

Income inequality has become a major topic of conversation in policy circles. While the rural communities we looked at tend to have lower scores on inequality overall, the numbers for some communities are still high. Income inequality is defined as the ratio of household income at the 80th percentile to income at the 20th percentile. Overall, the 2,243 counties we analyzed had an income inequality score of 4.4, below the national figure of 4.9. But the counties in the African American South and Native American Lands were exceptions.

Both community types scored above 5.0 on inequality, with the Native American Lands scoring the highest at 5.3. In both cases, the inequality, again, primarily stems from income differences between racial/ethnic groups. The inequality number is lower in the other big minority community type we studied, Hispanic Centers. In those communities, the inequality number, 4.5, was just above the overall rural number and below the national figure. That may be because those communities tend to hold more and better job opportunities. Certainly, we saw this in Finney County, Kansas.

Yet the larger trend in the data is that income inequality is a less prominent concern in rural America than it is in the nation as a whole. That’s the good news. The more complicated point is that such greater equality may be due to a lack of high-income households in rural America.

Occupations and Employment Opportunities

Behind some of the income differences in the 2,243 counties we looked at are differences in the industries that dominate. Rural America may be seen as the land of rolling fields and tractors, but in reality, agriculture is not a big driver of employment in most rural communities. In fact, the biggest employer in all the communities we examined was “educational service, health care, and social assistance.” More than 20% of the people in every community worked in this field, though the largest percentage of those working in the Aging Farmlands, 21%, are tied to agriculture.

In many rural communities, the schools and/or the hospital, if there is one, are the largest employers and town anchors. These institutions can’t easily close when the economy takes a downturn or pull up stakes for better opportunities elsewhere. It’s one reason these assets are crucial to their communities.

Beyond that category of work, manufacturing is still a leading employer in many of the 2,243 counties we studied. The sector accounts for 16% of the jobs in Rural Middle America and the Evangelical Hubs, 15% in the African American South and 14% in Working Class Country. Retail is also a big industry in a number of the county types. And agriculture plays a major role in the Aging Farmlands (21%), Hispanic Centers (16%), Native American Lands (10%), and LDS Enclaves (10%). In every other type, agriculture accounts for 6% or less of employment.

The Native American Lands stand out for having a higher number of jobs in “public administration” (11%), but that is due in part to the federal employees living in those communities.

The rising service sector is also less of a story in rural America. That’s because retail trade tends to have a smaller role in these communities. Smaller populations have meant fewer stores for decades and online shopping has added to that story. Online retail has also had a special impact in these communities, giving rural consumers choices they have not had available to them historically when there were one or two small stores downtown or a Walmart in the town nearby. In many of these communities “shopping local” has long offered limited options.

Education, Unemployment, and Poverty

Any serious discussion of the economy cannot exclude the important role educational attainment plays in a community’s hopes for growth and a better future. Data show the gap growing in the earning potential between those with an education beyond high school and those without one. In 2015, an analysis of Census data found that college grads earned 56% more than those whose highest level of education was a high school diploma.

A 2017 analysis form the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that the difference in weekly earnings between those with a high school diploma and those with just some college experience was $62 — that’s more than $3,200 a year, and the numbers climbed sharply as the education levels increased.

Higher levels of education, however, serve more than the workers; they serve the community as well. A better-educated populace is more likely to draw new employers and more good-paying jobs, a goal for many rural communities. Businesses increasingly want well-trained and skilled workforces that can adapt to a fast-changing economy.

And the data show educational attainment is one important area where rural America stands apart from the rest of the country. Overall, 54% of those between the ages of 25 and 44 have some time in college under their belt. That is 11 points lower than the 65% national figure for that age group. Again, however, the figures vary greatly by community type.

The numbers are particularly low in the rural communities with large populations of color. In the African American South, Hispanic Centers, and Native American Lands, the figure is under 50%. But the numbers are above 60% in Rural Middle America, the LDS Enclaves, and the Aging Farmlands, where the “some college” number sits at 68%.

Those numbers belie some of the common misconceptions about rural communities as places where education is not a top concern. The most rural of our rural county types have higher rates of educational attainment than the nation as a whole. But they also show that concerns about lower education rates among people of color should not be contained to just urban places. Again, reductionist views of rural America miss the larger point: that single solutions to challenging social problems are likely to be ineffective in rural America. While higher educational attainment is a goal for all communities, there are varying levels of need in rural communities.

Using the broadest measure of the 2,243 counties we examined, unemployment in rural America roughly matches the national average. The national unemployment rate was 4.4% in 2017, with the rural America clocking in at 4.5%. But the similarity in numbers masks a lot of nuance. In some communities, the rate was below the national figure; in others, it was above. In both cases, the percentages differed substantially among the various county types.

In the Aging Farmlands, LDS Enclaves, and Rural Middle America, the unemployment rates were 4% or lower. But in the African American South and Native American Lands, the figure stood at 6%. More interesting, the figures here don’t seem to have a common driver. For instance, the Aging Farmlands and Rural Middle America are driven by different industries (agriculture and manufacturing) and are at opposite ends of the population density scale. What’s behind the differences?

Education stands out as a factor. The three community types with the highest rates of educational attainment also have the lowest unemployment rates. The three community types with the highest unemployment rates are also below the rural America average for some college. Those data suggest that one of the best ways to help the many different economies of rural America may be to invest in improving education. An effort to make at least some time at a community college part of community expectations could be a boon to local chambers of commerce — and building relationships with those schools could pay dividends.

The one exception seems to be Hispanic Centers, which have the lowest educational attainment rates but also have an unemployment rate that matches the national average and rural America median. The vibrancy of these economies is a key reason. Many tend to be small urban hubs in larger rural areas, places that are commercial centers often with a base around agriculture processing.

When it comes to children living in poverty, the connections between educational attainment and economic opportunity are clearer.

A third of children in the African American South and Native American Lands live in poverty. The same is true for a quarter of the children in Hispanic Centers. The rates are far lower in the Aging Farmlands, Rural Middle America, and LDS Enclaves.

Financial Well-Being

Financial well-being in rural America on the whole could be improved, but there are clear fissures among different kinds of communities, according to Gallup’s recent well-being research. Note that Gallup’s breakdown encompasses all 3,100-plus counties across America. Here we zero in on the nine rural types.

At least 40% of residents in rural-oriented communities have worried about money in the past week. The most rural community types — Native American Lands and Aging Farmlands — have the highest rates at 45% each. The African American South, Working Class Country, and LDS Enclaves are close behind at 44%; Evangelical Hubs report 42%; while Hispanic Centers, Rural Middle America, and Graying America stand at 40%.

What makes this worry more tangible: More than 15% of people in predominantly rural community types say they do not have enough money to buy food. The variance runs from roughly 30% in predominantly African American, Hispanic, and Native American communities to under 20% in more moderate-income, predominantly white ones.

To be clear, none of these numbers are completely explanatory or determinative when it comes to the economic opportunities and challenges in rural America. For instance, unemployment rates may be low and education rates high in the Aging Farmlands, but there are unique challenges in those places as we heard when we visited Gove County, Kansas. High land prices combined with a trend toward massive acreage have made it tougher for young people to get started and stay in their hometowns. And while there are deep challenges in some Native American Lands, there are also innovative approaches to economic development in some communities, as illustrated by REDCO’s work in Todd County, South Dakota, home of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe. (See our community profiles on Gove and Todd counties.) Meanwhile, many of the Hispanic Centers, are seeing population growth with young non-native families and schools that need to focus on students coming from homes where English may not be spoken.

Any plan to spark economic development and change in rural America has to take those differences into account.

Infrastructure: Real World and Virtual

For an economy to thrive, people and ideas and products have to be able to move in the physical world and online. That imperative can be a challenge in rural communities. In those locales, acreage is often vast and the connections between cities, towns, and homes can be tenuous. Fewer people usually means fewer roads, and lower population densities tend to lead to less interest from telecommunications companies to hardwire homes. Those trends are clear in the data, but so are marked differences at the community-type level.

Looking at miles of road, the median rural counties in the LDS Enclaves and Rural Middle America types are at the high end of our sample at 1,273 miles and 1,152 miles respectively. At the other end of the spectrum, the median counties for the African American South and Working Class Country are not even at 900 miles of road.

More interesting in the road data, however, is the lack of a correlation between people and mileage. For instance, the community type with the highest median population, the Evangelical Hubs with more than 23,000 people, has some of the lowest numbers for miles of road at 990. Meanwhile, Rural Middle America, with a median population of more than 22,000, has a median road miles number of 1,152 — that’s 16% higher.

Some of this divide is regional and might be explained by state-level decisions on resources. The communities of the African American South also have relatively high population numbers, a median of more than 20,000, and very low numbers for miles of road. One key element they share with the Evangelical Hubs: They are largely based in the Southeast. The greater miles of road in the Aging Farmlands is also noteworthy, especially considering the low populations of those places. Perhaps it is a sign of communities that understand the importance of transportation in places that live and die by the ability to move commodities from farm to market.

When it comes to digital infrastructure, the picture is nuanced. In terms of broadband Internet access, the rural counties in our analysis do quite well on mobile connections. In all rural types, the median county has at least 98% of the population with a 5 megabytes-per-second download speed and 1 megabyte-per-second upload speed, the Federal Communications Commission’s definition of mobile broadband.

Those high mobile broadband penetration numbers are not a surprise when you visit rural communities. Even in remote locales, the mobile Internet is often the dominant connection to the outside world, for everything from road closures to crop prices.

But when the conversation shifts to a fixed connection, with much faster speeds of at least 25 Mbps per second on downloads and 3 Mbps per second for uploads, the numbers look very different. There are sharp differences across the 2,243 counties. The broadband deployment numbers in Rural Middle America, 85% of the population, are not far off from the overall U.S. figure, 94%. But the figures for other community types are much lower. In the Native American Lands, the figure is 58%. In the African American South, the figure is 68%.

But the digital divide in rural America is not just about racial and ethnic differences. The median broadband figure for the Hispanic Centers, 80%, is much higher than largely white Evangelical Hubs, which sit at 69%. That may be something of a surprise considering that the Evangelical Hubs are among the more densely populated communities in our rural sample.

In general, however, our rural counties lagged the national figures on fixed broadband deployment — some by large percentages. And in a world where everything from entertainment to work can be contingent upon a strong Internet connection, that rural lag can add to the challenges for communities that are trying to attract people and employers.

Online News and Social Infrastructure

Even with those differences and challenges in rural America, however, one tech outlet holds immense power across all the different kinds of communities we examined: Facebook. In every one of the nine rural community types, more than 40% of the people report that they visit Facebook at least once a month, according to data from the consumer research firm Simmons-MRI.

Those numbers stand out across the board in these communities when compared to other social media and news sites — from Craigslist and Twitter to FoxNews.com and CNN.com. And the comparisons aren’t really close. FoxNews.com and Twitter tend to be in the very low double-digits. Craigslist is a little higher, but doesn’t break 20% anywhere.

Facebook has become something of a one-stop everything shop in rural America — a place to keep up with friends and headlines in communities where the local newspaper has taken a hit. In smaller communities, Facebook also serves as the local yellow pages, with local businesses using the platform to host their sites. In Todd County, our Native American Lands county, we heard how people’s Facebook pages are sometimes the most reliable ways to reach them. It is the online address that never changes. Facebook may not be a government entity, but in rural America is almost serves as a public utility.

In a larger sense, these financial, employment, and infrastructure data show that there is no single, cohesive rural American economy. The 2,243 counties sit in different situations, are driven by different industries, and face different challenges.

Housing Strides and Strains

If a person’s home is often their largest investment, rural America sits in a different place than much of the nation. For the most part, these communities did not experience the housing boom that the rest of the country did in the first half of the last decade.

The median housing value in all the types we looked at was under $200,000 — and in some places, the value was far under that amount.

For instance, in Hispanic Centers, Native American Lands, Evangelical Hubs and the African American South, the median home value was less than $100,000. That gives some indication of the wealth in these communities and of a big challenge they face. Lower values mean less for the community to collect in property taxes and less individual home value for residents to borrow against.

There are, however, some upsides to those lower values, a big one being higher home ownership rates. Less valuable homes also mean more affordable homes overall. In our 2,243 rural counties, roughly 75% own their homes. That compares to a national rate of about 64%.

There are some notable differences across rural America. The Native American Lands have the lowest home ownership rate at 63%, while Aging Farmlands, Working Class Country and the LDS Enclaves are all above the 75% figure. That’s a key anchor for citizens. It’s harder to leave a community when one is a homeowner. And selling a home in a place with a declining population can be difficult.

When it comes to severe housing problems, including overcrowding, high costs, and the lack of kitchen or plumbing facilities, the disparity between communities of color and mostly white communities comes into view. Consider the 9% rate in Aging Farmlands, compared with the 21% rate in Native American Lands — and both community types are 100% rural. The U.S. overall average for housing problems stands at 18%. This suggests opportunities to build affordable housing in Native American Lands, where the population is growing. In the Aging Farmlands, where populations tend to be declining, housing rehabilitation could take priority.

Homes in rural America tend to be at least 40 years old. Many older homes are found in whiter communities with older residents. For example, the medians in Aging Farmlands and Rural Middle America top the 50-year mark; Graying America bucks this trend.

Median Age of Home Structures by Community Type

| Aging Farmlands | 1959 |

| Rural Middle America | 1965 |

| Hispanic Centers | 1975 |

| Graying America | 1978 |

| Native American Lands | 1978 |

| Evangelical Hubs | 1979 |

| Working Class Country | 1979 |

| LDS Enclaves | 1979.5 |

| African American South | 1980 |

New housing units are most robust in two younger and older predominately white communities: LDS Enclaves, where more than a quarter of the population are under 18, and Graying America, where about a quarter of the population are 62 or over. The most rural places, Aging Farmlands and Native American Lands, have seen the fewest new units.

Daily Life and Health Care

A widespread belief swirls that rural Americans grow and raise a lot of their food, and therefore have better food access. This is not the case. The Food Environment Index, which takes into account distance to the nearest food market as well as income, ranges widely in the ACP rural universe. It’s highest in Rural Middle America at 8.2 and lowest in Native American Lands at 4.9. In the African American South, where the median household income is also lower and resources seem less abundant, it’s 6.4. Meanwhile, in the Aging Farmlands, dominated by agriculture but where exporting food to other markets is the focus, the index is 7.6. This matches the median for all nine county types in rural America. In the U.S. overall, the median is 7.7.

Health-Care Gaps

Lack of health-care access is a significant pain point across rural America. For example, uninsured rates reveal a wide disparity, with white communities faring much better than communities of color. The medians by community type are below.

Hospital closures, a prevailing concern in rural America today, also vary depending on community type. Evangelical Hubs have suffered the most with 28 closures, and the African American South next with 18.

The rural hospital issue has garnered a lot of attention in recent years, and the Center for Optimizing Rural Health has examined the situation in great detail, for those interested in learning more or addressing this problem.

When a hospital closes in a rural community, the impacts stretch beyond health. An analysis from the Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank looked at communities with hospital closures between 2011 and 2016 and found subsequent declines in economic growth and net employment in those communities. Communities without closures saw their economies and net employment grow in that time.

Considering the employment data we cite in this report, those numbers are not a surprise. In every one of the nine rural community types we visited, “educational services, and health care and social assistance” was the No. 1 industry for overall employment. (It was tied for first in the Aging Farmlands.) Closing down a rural hospital kicks a leg out from under the economy in many rural places. It takes away an institution in places where those kinds of employers can be scarce.

Along the lines of limited care access, the number of primary physicians and dentists per population also varies depending on the kind of rural community in question. For seven of the eight community types, a median of one doctor serves more than 2,000 people. Only Graying America, where about a quarter of the population are age 62 or older, comes in under 2,000 people to one doctor. Compare those figures to the U.S. overall at 1,330 to 1. (Hover over the dots to see the population figures.) More rural telemedicine services could help to narrow this access gap. Meanwhile, Gove County, an Aging Farmland we visited, breaks the mold with five M.D.’s per 2,600 population.

The ratio of dentists to the rural population overall and within individual community types shows a more extreme difference than the ratio of primary care physicians. Half of the community types, including heavily African American and Latino communities, are above 3,000 to 1. Compare the rural figures to the U.S. overall at 1,460 to 1. (Hover over the dots for population details.)

Well-Being and the Future of Rural America

Key indicators show that community well-being is relatively strong in rural America, according to Gallup’s recent research. Again, note that Gallup’s breakdown encompasses all 3,100-plus counties across America. Here we look at the nine most rural types. Take community pride, for one. In all these county types, a clear majority express pride in where they live. Homogeneous LDS Enclaves, Rural Middle America, Evangelical Hubs, and Aging Farmlands climb to percentages in the high 60s and low 70s.

More than 70% of residents in rural county types report feeling safe and secure in their communities. Residents in nonwhite and more diverse communities do not feel as safe as populations in homogeneous, white communities.

There is a great deal of citizen engagement for community betterment happening in rural communities. At least 20% of residents in predominantly rural community types say they have been recognized for improving where they live in the past 12 months; nationally, the rate is the same. Only Aging Farmlands, which are 100% rural, outpace the pack at 28%. Graying America, the African American South, and Native American Lands come in at 22%. Working Class Country stands at 21%. Hispanic Centers, Evangelical Hubs, and LDS Enclaves report 20%.

Those are high scores on issues that people want addressed when they are looking for a community to call home, and these issues impact the many different kinds of rural community we studied in this report. All of which is to say, despite the challenges in some areas, rural America still has a lot to offer in 21st century America. Growing and serving it in a rapidly changing world, however, will require a new and more complex, granular understanding of the many kinds of community that define it.

To learn more about rural America and the county-level data in this report, visit:

- The Center for Rural Strategies, the nonprofit that aims to build opportunities for small towns and rural communities by building coalitions and partnerships, and by advancing strategies that strengthen connections between rural and urban places. The center also runs the Daily Yonder, an online news site devoted to rural America.

- The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s resource page on Rural Health and Well-Being in America, a collection of key research and emerging insights into the many factors that shape rural health in America.

- The Rural Health Information Hub, a federally funded national clearinghouse on rural health issues.

- The County Health Rankings and Roadmaps, the comprehensive annual analysis of health measures and their underlying factors, is a wealth of knowledge and the backbone of the data in this report.